The Blakean Metaphysic, by Joel Meyer

As true vision perceives the very essence of reality, it cannot help but be metaphysical by nature. The difference with Blake is that, though he identifies different realms of reality, these are really only domains of knowing, making Blake’s metaphysic purely epistemological; indeed, methods of knowing form the philosophic crucible of Blake’s entire worldview, and are thus present in all aspects, symbolic or otherwise.

In order to re-awaken Albion, or the creative humanity complete in itself, we must realize a “spiritualized” mode of seeing, an active epistemic that appears in direct and intended contrast to the passive sense impressions of empirical science. This is reality itself, as Blake affirms: “Imagination is not a State: it is the Human Existence Itself.” The Gospels, and the prophecies found in Ezekiel, Acts, and the Book of Revelation, are all higher forms of this true divine vision, graciously preserved in their purity, and altogether characterize the Biblical tradition that Blake wishes to exhume from its miserable tomb and to once more exalt on high. He ultimately wishes to see “Eternity in a grain of sand, And a heaven in a wild flower”; to see the infinitely beautiful in every single perception: this is precisely what he means by the spiritual, imaginative vision.

Although this is a grand and visually lofty idea, it is hardly the sole, exclusive type of “re-awakening”; it does, however, entail any other individual method, though its form might appear differently. Northrop Frye, the pre-eminent Blake scholar, says that “there are exactly as many realities as there are men”. This leads us to another central idea: The differentiation between “General Forms” and “Minute Particulars”; Blake believes that the former results in a spurious aggregate comprised of an array of particulars assembled by the “tools of Satan”, or “Memory”, and “Ratio”, or fallen reason. This is when the individual loses its particular vitality and is crudely absorbed into the monstrous generality, which cares only for an equality en masse and not for the specific needs of its members.

Blake encounters an essential problem early on when he tries to visualize just how the individual becomes part of the greater “universal Humanity” while yet retaining his identity; some have said of him in regard to this complexity: “Bake is a dualist who wants and tries to be a monist.” Whether he ever truly solves this problem is debatable, but this question is important to keep in mind. For the present, it is to be known that Blake’s most ambitious goal in this regard is to preserve a man’s particular reality whilst according it to the overall humanity, and not losing his identity to abstraction and generalities in the process.

The declaration, “As a man is So he Sees,” helps us in comprehending that subject and object are not two different things but one inseparable reality. If we visualize the external world in terms of our own internal understanding, what is the mundane reality but the physical extension of our own ideas? The old philosophical proverb, esse est percipi, or being is perception, applies immediately to the present context, as nothing really is if it is not attached with a particular identity deriving from our highest sense, viz. imagination. Thus we can see how a proper delineation of the sacred and the profane takes place; when something is spotted and brought into artistic detail by imaginative vision, it is bequeathed with a certain sacrality; and when something is obscure and irrelevant to everything but the sensual, it is deemed illusory and thus profane.

Another important idea related to Blake’s metaphysic / epistemic, returning to the notion of a dualistic monist, is his view of the conditional duality of the physical dimension. Throughout Blake’s work we find hints to a theory of opposites, where they agree and where they conflict, but nowhere is it more thoroughly considered than in his iconic poem, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Within the text, Blake posits two seemingly irreconcilable sides or factions that are always opposed; and yet they are equally necessary. The problem that Blake sees is that one of them will overcome the other in power and become absolute, inheriting a tendency to ostracize its opposite in moralistic terms, resulting in a deep “psychological” repression of the conquered faction. Blake makes the attempt to show that neither are inherently Good or Evil, but merely a different side of the same coin, so to speak, and that our progress is inherently linked to the maintenance of these opposites.

This has been a very broad brush-stroke of some gigantic themes, and by no means an exhaustive exposition of “the Blakean metaphysic”; but now the reader will be acquainted with several of Blake’s primary themes, allowing us to fill in the details with much greater ease. In closing, it is remarkable to note the very method Blake uses in his engravings, or corroding away the excess to reveal the imprint, is a direct parallel to Blake’s artistic assault on the philosophical pedantry and the social caprice of his day; it might be said, perhaps, that Blake had learned how to “philosophize with a hammer” before that caustic philologist had even been born…

“But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul is to be expunged; this I shall do by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.”

~ The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Meditations On Whirlpools (Dabbling in Process Philosophy)

“Familiar things happen, and mankind does not bother about them. It requires a very unusual mind to undertake the analysis of the obvious.”

~ Alfred North Whitehead

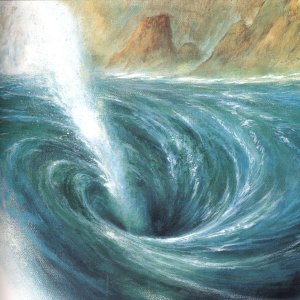

Consider something most everyone has seen at some point in their lives. When we take a walk by a creek, or dip an oar into the water when we are in a rowboat, we quite often see the little, spinning, roughly vertical patterns called whirlpools. These dynamic patterns are plainly obvious, yet bring some very interesting metaphysical and phenomenological questions to mind.

Consider something most everyone has seen at some point in their lives. When we take a walk by a creek, or dip an oar into the water when we are in a rowboat, we quite often see the little, spinning, roughly vertical patterns called whirlpools. These dynamic patterns are plainly obvious, yet bring some very interesting metaphysical and phenomenological questions to mind.

A whirlpool is a kind of phenomenon that is best described as an event, or a process, rather than an object or “thing” with some kind of essential nature. What material makes up a whirlpool? Water? A whirlpool is a frictional vortex; water spins and twists around and within it, cycling through it continuously. Due to the dynamic, whirling motion of the system, no molecule of water exists in the same relation to the organic whole of the whirlpool for any period of time. Indeed, the shape of the dip, “tube”, or “shaft” of a whirlpool never twice exhibits the same shape, while the location of the visible pattern in the vortex (a system more complex, and larger, than that part of it that is visible) is constantly in flux as well. It is nigh impossible to describe a whirlpool in terms of the material that constitutes it, since it is not really an object (except of perception) and involves new material at every instant. Inasmuch as it is an object of our experience, we impose a phenomenal constancy on the ever-changing pattern that we observe ongoing similarity (similarity being an important concept to keep in mind in this case) in, but the “material” involved is constantly changing and the actual shape, form, or pattern of the event is constantly changing. It is as if we can only understand this seemingly simple phenomenon as a kind of “regional, experiential event”, to be described as physicists now do electrons, which they conceptualize as having no definite locations but rather as being probabilistic spatial-temporal regions that exhibit certain adjectival qualities.

Our understanding of the whirlpool cannot be understood as unrelated to all in contact with it, either directly or indirectly. There is no definite line where a vortex begins and ends. All water molecules in the body of water a whirlpool obtains in are pulled down toward the “base” of the vortex (if ever such a point could be located), the degree to which they are affected depending on their distance from the event. If we wish to abandon the language of causal connection, as may be warranted, we can say that we observe the repeating pattern that the water molecules move toward the base of the whirlpool seemingly in the degree to which they are close to its epicenter. The vortex being understood as an ongoing event or process, then, rather than a distinct “entity”, all the water molecules in the entire, connected body of water participate in the whirling of the whirlpool. Thus, the whirlpool can be understood verbally, as a working or doing of the whole aqueous (and beyond) world it obtains in. It is a fleeting, living mode — having birth, life, and death — of a whole organism (however we are going to define that whole).

In much the same way, living, biological organisms can be understood as adjectival-verbal sorts of things, as events rather than object-beings. They cannot be understood in terms of the matter that composes them, since that changes and we yet regard the whole system as the same. (Note as well that this refers only to what we regard as having constancy, irrespective of any “actual” constancy that would obtain in the realm of the Nous, an utterly inconsistent concept in the first place.) Nor can they be understood strictly in terms of the forms or shapes they take, since these too are subject to flux while the “essential” whole is yet regarded as constant. So for these “entities” to “exist” (a poor word, though one we are compelled to use at this point), it is necessary that they be regarded by a subject. Different subjects’ interpretations of both the duration and location of an event is bound to vary; at best living objects may be regarded as regions, fields, in space and time, with probabilistic “locations” like electrons, and connected with the whole world they obtain in. Indeed, Spinoza may well be correct in his assertion that every particular is a mode of the “One”, the whole of Being, to be understood adjectivally or verbally, rather than essentially or objectively.

The analysis also applies to non-living “things”, down to the smallest of atoms and subatomic particles (which can be understood consistently as both waves and particles). They are adjectival, verbal, describing the working of Being (if such a thing is even a coherent notion) in an indeterminate region of time and space, and connected with the entire, organic whole of Being. Again, “things” as we know them — especially living, biological organisms — can be understood better by conceiving of them as complexes drives, urges, and wills, as tendencies toward rather than beings unto themselves. A whirlpool is a tendency in water toward a given arrangement, and one that happens in a given way. It is the way water becomes in this case that makes a whirlpool what it is, just as it is the way the organic whole of Being becomes that makes us what we are. We are becomings who will not admit their not being beings unto themselves.

Subjects impose a constancy on the chaos and flux, and this determines the so-called “existence” of objects. Particular existence is an artificial, alien notion, in that it represents an attempt to depart from the organic conception of Being as an entirely connected, natural whole. Essential qualities are a sham, as far as we know now; therefore, we live not in a world of “things” but, rather, in an adjectival-verbal world of events, a world of ever-spinning whirlpools.

leave a comment