Meditations On Whirlpools (Dabbling in Process Philosophy)

“Familiar things happen, and mankind does not bother about them. It requires a very unusual mind to undertake the analysis of the obvious.”

~ Alfred North Whitehead

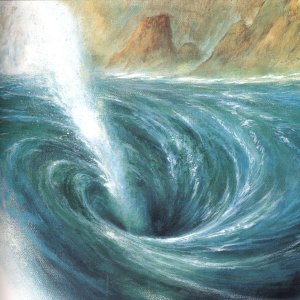

Consider something most everyone has seen at some point in their lives. When we take a walk by a creek, or dip an oar into the water when we are in a rowboat, we quite often see the little, spinning, roughly vertical patterns called whirlpools. These dynamic patterns are plainly obvious, yet bring some very interesting metaphysical and phenomenological questions to mind.

Consider something most everyone has seen at some point in their lives. When we take a walk by a creek, or dip an oar into the water when we are in a rowboat, we quite often see the little, spinning, roughly vertical patterns called whirlpools. These dynamic patterns are plainly obvious, yet bring some very interesting metaphysical and phenomenological questions to mind.

A whirlpool is a kind of phenomenon that is best described as an event, or a process, rather than an object or “thing” with some kind of essential nature. What material makes up a whirlpool? Water? A whirlpool is a frictional vortex; water spins and twists around and within it, cycling through it continuously. Due to the dynamic, whirling motion of the system, no molecule of water exists in the same relation to the organic whole of the whirlpool for any period of time. Indeed, the shape of the dip, “tube”, or “shaft” of a whirlpool never twice exhibits the same shape, while the location of the visible pattern in the vortex (a system more complex, and larger, than that part of it that is visible) is constantly in flux as well. It is nigh impossible to describe a whirlpool in terms of the material that constitutes it, since it is not really an object (except of perception) and involves new material at every instant. Inasmuch as it is an object of our experience, we impose a phenomenal constancy on the ever-changing pattern that we observe ongoing similarity (similarity being an important concept to keep in mind in this case) in, but the “material” involved is constantly changing and the actual shape, form, or pattern of the event is constantly changing. It is as if we can only understand this seemingly simple phenomenon as a kind of “regional, experiential event”, to be described as physicists now do electrons, which they conceptualize as having no definite locations but rather as being probabilistic spatial-temporal regions that exhibit certain adjectival qualities.

Our understanding of the whirlpool cannot be understood as unrelated to all in contact with it, either directly or indirectly. There is no definite line where a vortex begins and ends. All water molecules in the body of water a whirlpool obtains in are pulled down toward the “base” of the vortex (if ever such a point could be located), the degree to which they are affected depending on their distance from the event. If we wish to abandon the language of causal connection, as may be warranted, we can say that we observe the repeating pattern that the water molecules move toward the base of the whirlpool seemingly in the degree to which they are close to its epicenter. The vortex being understood as an ongoing event or process, then, rather than a distinct “entity”, all the water molecules in the entire, connected body of water participate in the whirling of the whirlpool. Thus, the whirlpool can be understood verbally, as a working or doing of the whole aqueous (and beyond) world it obtains in. It is a fleeting, living mode — having birth, life, and death — of a whole organism (however we are going to define that whole).

In much the same way, living, biological organisms can be understood as adjectival-verbal sorts of things, as events rather than object-beings. They cannot be understood in terms of the matter that composes them, since that changes and we yet regard the whole system as the same. (Note as well that this refers only to what we regard as having constancy, irrespective of any “actual” constancy that would obtain in the realm of the Nous, an utterly inconsistent concept in the first place.) Nor can they be understood strictly in terms of the forms or shapes they take, since these too are subject to flux while the “essential” whole is yet regarded as constant. So for these “entities” to “exist” (a poor word, though one we are compelled to use at this point), it is necessary that they be regarded by a subject. Different subjects’ interpretations of both the duration and location of an event is bound to vary; at best living objects may be regarded as regions, fields, in space and time, with probabilistic “locations” like electrons, and connected with the whole world they obtain in. Indeed, Spinoza may well be correct in his assertion that every particular is a mode of the “One”, the whole of Being, to be understood adjectivally or verbally, rather than essentially or objectively.

The analysis also applies to non-living “things”, down to the smallest of atoms and subatomic particles (which can be understood consistently as both waves and particles). They are adjectival, verbal, describing the working of Being (if such a thing is even a coherent notion) in an indeterminate region of time and space, and connected with the entire, organic whole of Being. Again, “things” as we know them — especially living, biological organisms — can be understood better by conceiving of them as complexes drives, urges, and wills, as tendencies toward rather than beings unto themselves. A whirlpool is a tendency in water toward a given arrangement, and one that happens in a given way. It is the way water becomes in this case that makes a whirlpool what it is, just as it is the way the organic whole of Being becomes that makes us what we are. We are becomings who will not admit their not being beings unto themselves.

Subjects impose a constancy on the chaos and flux, and this determines the so-called “existence” of objects. Particular existence is an artificial, alien notion, in that it represents an attempt to depart from the organic conception of Being as an entirely connected, natural whole. Essential qualities are a sham, as far as we know now; therefore, we live not in a world of “things” but, rather, in an adjectival-verbal world of events, a world of ever-spinning whirlpools.

Speculation on Being, Becoming, Fate, and Striving

“This is our purpose: To make as meaningful as possible this life that has been bestowed upon us; to live in such a way that we may be proud of ourselves; to act in such a way that some part of us lives on.”

~ Oswald Spengler

When we step outside pure analytic philosophy and examine not only our own experience, but that of all other living organisms in our experience, certain facts come to mind. The following constitute a little bit of speculation, linguistic arrangements organized in such a way that a glimpse of the ineffable may be had, with some effort. I am not aiming at Truth, but rather wisdom.

When we step outside pure analytic philosophy and examine not only our own experience, but that of all other living organisms in our experience, certain facts come to mind. The following constitute a little bit of speculation, linguistic arrangements organized in such a way that a glimpse of the ineffable may be had, with some effort. I am not aiming at Truth, but rather wisdom.

- We possess no being, yet we strive for it. There are many interpretations of Nietzsche’s assertion that life is Will to Power, as that perspectivist philosopher might have expected. One such interpretation may be that living things — perhaps best analyzed as biological complexes of drives, urges, and wills — are not “beings” per se but rather becomings, striving continuously, dynamically toward Being. Life struggles against all that would contain it in a desperate, and ultimately fatal, attempt at permanent impression ever outward from itself. Degeneracy, a physiological weakness, comes about when the striving toward Being takes the form of attempting to reach Being by means of destroying the self, that an immaterial and permanent “Being” might be attained — denial of the world into which life is thrown.

- “A nihilist is a man who judges of the world as it is that it ought not to be, and of the world as it ought to be that it does not exist,” wrote Nietzsche in a passage published in The Will to Power after his death. Nihilism is a result of physiological degeneracy, judging the actual world of Becoming as inferior to, or a shadowy reflection of, a sublime, non-spatiotemporal Realm of Forms, Ideas, Being. Thus Platonism, and Christianity, point toward nihilism in their rejection of Becoming, of the Flux that is necessitated by a general “absence of essence”.

- If we are to accept as a premise that there are no such things as “essential qualities”, we may take one of two routes, as far as I can see. The first option is that nothing — in the sense of “no [particular] thing” — exists in the sense of having Being, full stop. The second option is that all ephemeral things are essentially identical in that they share the one and only essential quality, that of Being.

- Democritus, the atomist, was the Laughing Philosopher because he understood that we humans are lumps of matter that cannot admit they are matter. Heraclitus, the flux theorist, may well have been the Weeping Philosopher because he understood we are Becomings constantly seeking after an individuated Being that cannot be realized, insisting against all evidence that we are the same that we were a second before, tragically fated to fail at attaining our ultimate task: Permanence.

- We humans seem to be the only living species the members of which understand they will perish. We know that the Being we — as living things — seek after is elusive, that the task before us is utterly impossible, Sisyphean. Yet we continue to strive toward it, either toward a sense of Being or toward a cessation of the Becoming we experience, by means of creativity, procreation, or religion in the first instance, or suicide in the second. Both routes ultimately take us to the same place, nothingness. What this suggests is that we can never change our ultimate destination, but we can change the ways of Becoming by which we reach it.

Nothing particularly profound has come out of this discussion, but it is interesting to see what one does with the thoughts floating around in one’s mind. Heraclitus and Nietzsche, two of my favorite philosophers, have put all the ideas here better, but one has to start from somewhere.

Nothing particularly profound has come out of this discussion, but it is interesting to see what one does with the thoughts floating around in one’s mind. Heraclitus and Nietzsche, two of my favorite philosophers, have put all the ideas here better, but one has to start from somewhere.

Before we can make as meaningful as possible this life that has been bestowed upon us, as Spengler tasks, we must make as much sense as possible of this life that has been bestowed upon us. With tools we know will fail us at the crucial point — nouns, verbs, words that refer at once to everything one can refer to, but also nothing, since they are not strictly connected with reality or, more accurately, experience — we set upon the parallel to the fatal task of striving toward Being: We try, desperately and with perfect knowledge of the impossibility of the project, to describe how it is that a continuity of experience can possibly obtain in a world of Becoming, or if such continuity is merely a “spook in the mind” (with thanks to Stirner). Is there any way out of skepticism, solipsism, nihilism?

leave a comment